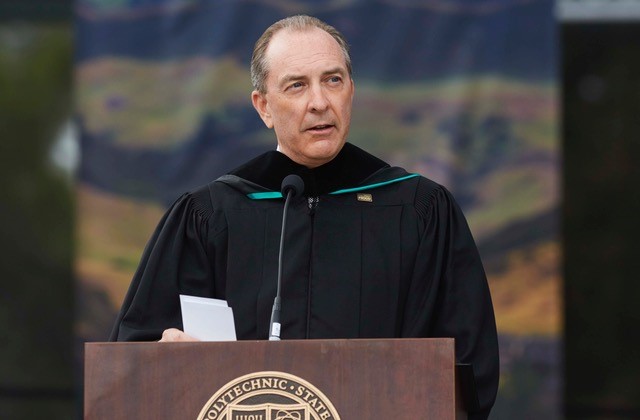

Long before he was CEO, before he was chairman of the board, before he’d even heard of Parsons, Charles L. Harrington, as a boy, developed a sense that he was somewhat different from his peers.

Part of that difference was his insatiable curiosity and drive. Chuck always nurtured a variety of interests, from playing basketball, tennis, and golf to waterskiing, woodworking, taxidermy, and scouting, even attaining the rank of Eagle Scout. Participating in so many activities gave him the opportunity to get to know people from all walks of life.

He was equally shaped by the work he did on his family’s farm in California. Chuck’s father, whose own father had died during the 1918 influenza pandemic, before he was born, always worried that he wouldn’t be around to see Chuck graduate from college. So he gave a walnut orchard to Chuck and told him if he worked it, it would pay for his college tuition. One day, Chuck could even take over the whole operation, which included rice, oats, barley, and wheat.

But taking over the whole operation didn’t happen.

Not because Chuck’s father’s concerns of an early demise were founded—but because his son-in-law had stepped in and had done so well at managing everything. That meant Chuck, away at California Polytechnic State University, would need to start job hunting.

Fortunately, Chuck had an outstanding college resume, so when he attended a job fair, offers from Chevron and Cargill came quickly. But it was the third offer that held the most allure. Parsons was at that job fair showing a film called Challenge of the Arctic. The video depicts Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, where enormous oil reserves were discovered on the North Slope and the trans-Alaska pipeline was built. Chuck watched that day in 1981 as the film told the story of how the Ralph M. Parsons Company completed the design, engineering, procurement, and construction of the Prudhoe Bay facilities under budget and ahead of schedule, despite unexpected ice blocks, perilous weather, and dangerous terrain.

Chuck was in.

Warren Mindheim, who hired Chuck, was one of the first friends Chuck made at his new job. He also became close with a few other ambitious up-and-comers that Warren had hired the year before. This “Brat Pack” ate lunch together every day, hung out both during and outside of work, and attended parties with professionals from Parsons, movie studios, and other large employers in the area. They also vigorously debated. Often. All of them strong-willed, they once got into a dispute about the dark side of the moon that Chuck settled with a Xerox copy and a picture of a moose.

In these early years at Parsons, Chuck’s personal life was evolving as quickly as his career, as he married his college sweetheart, Diane, and started a family in California with the first of what would become three children (a son and two daughters). Also carving out time at night after work to attend UCLA, he earned his MBA, graduating summa cum laude, with concentrations in finance and marketing.

Later, Chuck became the founding president of Parsons Commercial Technology Group. While leading this young group, he and a colleague got their hands on free tickets to a Charlotte Hornets game. Chuck had the idea to call the Southern Bell facilities group and inform them they’d won the tickets. When Southern Bell said they had a policy against accepting the tickets, Chuck, not to be deterred, said he’d love to come over and talk with them because he had some great ideas about how to better manage their 50 million square feet of facilities across nine southeastern states.

That conversation led to some small contracts, and when Chuck and his colleagues kept peppering Southern Bell, and their parent company, BellSouth, with even more ideas to reduce costs, improve schedules, and enhance quality across their portfolio, they eventually sent Parsons to examine their contracts in all nine states. When Parsons recommended consolidating those contracts, they agreed. The resulting contract ended up totaling over $100 million per year and a billion dollars in contract value, and after a competitive solicitation, was awarded to Parsons.

“The facilities team at BellSouth then recommended us to their outside plant network group, and we won another $250 million-per-year contract and had to build up a staff of 1,000 people doing outside plant engineering. And so we went from a small group of 30 people with less than $3 million in annual revenue to having these massive contracts overnight,” Chuck recalls. “It was a thrill.”

And what was the catalyst for these massive deals? A friend of Chuck’s father, Grover Connell, of the Connell Rice & Sugar Company, one of the largest traders of grain in the world, once relayed to Chuck a piece of wisdom: “I don’t ever lose. That doesn’t mean I always win. But I don’t ever lose.” That lesson was reinforced in group learning sessions at Duke University, where Chuck attended the Executive Education Program.

Insights like these have contributed to Chuck’s strategy and his success. Consider Parsons’ growth during his 13-year tenure as CEO. Despite the Great Recession, 2008, 2009, and 2010 were record years for Parsons in terms of revenue, profits, and cash flow. Even then, Chuck envisioned the enterprise moving from services to also include software and hardware and differentiating itself by emerging as a world-class technology company.

To get there, Chuck knew Parsons needed to invest. Soon came the $380 million SPARTA acquisition, which propelled the firm into cyber, space, intelligence, and missile defense. That acquisition changed the course for Parsons and paved the way for acquisitions to come: Secure Mission Solutions, then Delcan, followed by Polaris Alpha, OGSystems, QRC Technologies, Braxton Science & Technology Group, and, most recently, BlackHorse Solutions. Chuck felt that most of Parsons’ competition was baffled by what they perceived as strange choices. “They didn’t realize there was a whole strategy that backed up where we were going,” he says. Now, several years later, he sees those same firms realizing, “Wow, they’ve built this entire cyber, intel, space, geospatial, missile defense, ISR business,” which is now larger than the entirety of what Parsons’ federal business was at the time.

Part of what drove that strategy was a potent management style Chuck developed early in his career that he calls “dynamic tension,” which is the idea that dissenting opinions are a necessary driver of positive change. Never wanting groupthink, he welcomed diverse perspectives and recognized the importance of listening to everyone’s voice to keep innovating and to eliminate blind spots.

Chuck also learned the importance of authenticity. He’s built trust and inspired loyalty, even through hard times and tough decisions, by always being true to himself. In fact, it’s this winning tactic of always being true to yourself that he says is his most important advice for Carey Smith, his successor as Parsons’ CEO.

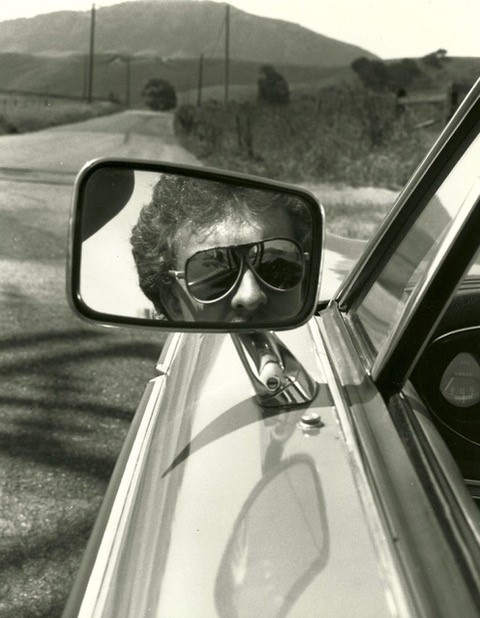

Now Chuck looks back at his long career at Parsons on the eve of retirement and claims, without hesitation, that what he’ll miss most are the daily interactions with people he’s come to view as part of his family. Never losing sight of the human element of Parsons’ work and the importance of making true connections, Chuck’s traveled around the world, often with his wife and kids in tow, drawing inspiration and insight from everyone he’s met along the way.

After more than a decade at the helm of the Parsons ship, Chuck has left an indelible impression. In his wake, he’s put his stamp on Parsons’ business, its culture, its reputation, and its brand. Of course, that should be no surprise when speaking of a man who says that rather than leave footprints in the sand, he’d leave them on the moon, where they’d last forever. Now, as Parsons is about to welcome its newest leader, if asked whether Carey should aim for the moon, as he did, he’d have only one possible response: “To infinity and beyond!”